Footnote 9 Doubt about the value of child migration was also expressed more widely in Parliamentary debates on the proposed Children Bill, with MPs including Somerville Hastings (the former Curtis Committee member) expressing reservations about the emigration of any unaccompanied children under school leaving age.

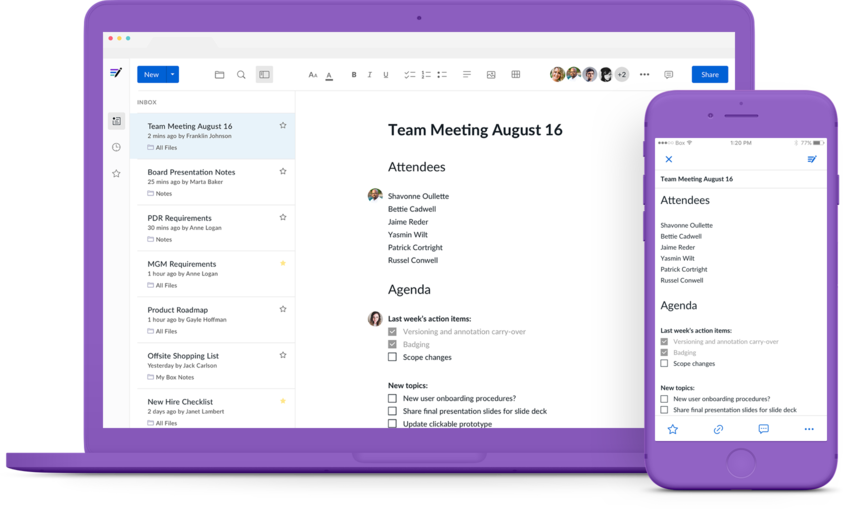

#Migrating simplenote to box notes professional#

Footnote 8 The Federation also published a pamphlet recommending that, in future, all sending organisations select children through formal selection committees involving professional social workers, that care should be taken to ensure that emigration was always in the best interests of the individual child and stating that ‘it should be borne in mind that it is a very serious matter to break a child’s home ties, however slender they may be’. Footnote 7 It found support too from the British Federation of Social Workers, whose President, Chair and Secretary wrote to the letters page of The Times commenting that they had ‘reason to think that the practices of the various agencies for the migration of children oversea vary and that their methods of selection of children, their welfare, education, training and after care in the receiving countries are not always of a sufficiently high standard’. Footnote 6 This call was also endorsed by the Young Women’s Christian Association of Great Britain, as well as by MPs in House of Commons debates during the passage of the Children Bill. Footnote 5 On the basis of the report, the Women’s Liberal Federation wrote to the Home Secretary to inform him that it had passed a motion calling for an inter-governmental commission of enquiry to ‘examine the whole system of the emigration of deprived children to British Dominions and overseas’. On the basis of concerns that old attitudes might still prevail in child migration work, Nobody’s Children recommended that an inter-governmental inquiry be set up specifically to consider the placement of child migrants in work, the after-care provided to them and the management of compulsory savings schemes for child migrants by receiving organisations. Footnote 4 Children sent overseas should have contact with someone equivalent to a Children’s Officer and contact with family remaining in the United Kingdom should be supported. It condemned attempts to tempt parents into consenting to their child’s emigration on the basis of unrealistically optimistic pictures of the life that might be possible for them overseas and argued that no child should be allowed to emigrate unless it were in their individual interests and that good standards of care, staffing and training would be provided. However, it claimed that ‘deplorable notions of child care’ still persisted in some organisations involved in sending and receiving child migrants, and argued that no child should be emigrated if they had parents able to make reasonable provision for them in this country. Footnote 3 Part summary and part commentary on the Curtis report, Nobody’s Children accepted the view of the Curtis Committee that emigration might be appropriate for some children under particular circumstances. In May 1947, The Liberal Party Organisation Committee on the Curtis Report published Nobody’s Children: A Report on the Care of Children Deprived of Normal Home-Lives. More co-ordinated public criticism of child migration also began to develop. The chapter considers why Moss-a former member of the Curtis Committee-took this view, and how broad policy standards such as the Curtis report were, in practice, interpreted and implemented in different ways. This decision was also informed by an independent review of child migration to Australia by John Moss, published in 1953, which offered a broadly positive view of this work. Concerns about the legal limitations of these regulations and their effective power in safeguarding child migrants once overseas contributed to a subsequent decision in the Home Office not to introduce them.

The chapter examines how the process of developing these regulations was delayed through a complex bureaucratic process, with a final draft of the regulations not completed until 1954. With stronger concerns about child migration being expressed by some professional and voluntary organisations in Britain, in 1949 the Home Office began a process of drafting regulations for the emigration of children from the care of voluntary societies.

This chapter examines the wider policy context and administrative systems for child migration to Australia in the period 1948-1954.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)